Beyond our Backyards

“To change everything, we need everyone.”

Community-level climate action requires us to think beyond our backyards. Susan Kruse, C3’s Executive Director talks about the paradigm shift that needs to happen in conservation if we are going to meet our climate goals.

Photo credit: Alisdare Hickson on Flickr

Community-level Climate Action Requires us to Think Beyond our Backyards

The climate crisis is deepening, and localities in Virginia can provide a crucial climate solution by building more dense and livable cities. Will environmentalists champion this solution or prevent its progress?

Let’s look at how the population has changed over the past ten years across the Commonwealth. Beginning in my home City of Charlottesville, the population has grown by 8%, while the population in surrounding Albemarle County has grown by 11%1. In Richmond, the population has grown by 10%, while adjacent Chesterfield County grew by 13%2. The same trend holds for many other cities and neighboring counties in Virginia. Counties are growing faster. The result is more urban sprawl, greater loss of forests and farmlands, longer commutes, and ever-increasing transportation emissions.

To reduce our greenhouse gas emissions and prepare for carbon neutrality, our cities cannot ignore our state’s projected population growth of nearly 1.2 million more residents over the next 20 years.3 Instead, our cities must grow faster than our counties, and that means two things need to change — density and affordability.

Moving from a Conservation to a Climate Mindset

For much of the history of conservation, advocates have spent their time advocating for where people shouldn’t live, for understandable reasons. Most of the wild places in the Eastern United States were decimated by the early 1900s. Ancient Eastern forests were clearcut, and several species, most notably the Passenger Pigeon, were slaughtered to extinction. As a result, our century-old forests now account for only 7% of forest cover in the United States.4

In response, President Teddy Roosevelt doubled the size of the National Park system at the urging of his friend John Muir. In 1905, Roosevelt also established the US Forest Service to manage National Forest lands and appointed Gifford Pinchot to lead the agency. These leaders, however, have a complicated legacy. What started as a good instinct to conserve nature quickly became entangled with an instinct to protect white values and culture.

Roosevelt and Muir had a well-documented dislike for Native Americans, and the creation of the National Parks also included the forced removal of Native populations from parkland and onto Reservations. Lakota Spiritual Leader Black Elk remarked at the time, “The United States made little islands for us and other little islands for the four-leggeds, and always these islands are getting smaller.”5

Pinchot was a devout follower of Madison Grant whose book, “The Passing of the Great Race or The Racial Basis of European History,” launched Eugenics and was touted by Adolf Hitler as “my bible” more than a dozen years before World War II.6

“While the conservation of forests, farmland, and urban tree canopies is admirable and lives in the heart of every environmentalist, we should understand that these goals can become entangled with policies that benefit white communities and harm Native Americans, Black, immigrant, and low-income communities. ”

You don’t need to look far into our past to find disturbing links between the laudable conservation of nature and the insidious conservation of white supremacy. In 2004, John Tanton, founder of the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR), nearly succeeded in electing an anti-immigrant majority to the Sierra Club’s Board of Directors. He's quoted as saying, “I’ve come to the point of view that for European-American society and culture to persist requires a European-American majority, and a clear one at that.” He only failed after the Southern Poverty Law Center sent a letter to Club leaders documenting FAIR’s links to hate group activity and warning that white supremacists were poised for a takeover. 7

John Tanton was the racist architect of the modern anti-immigrant movement. Photo credit: Southern Poverty Law Center

Thinking Beyond our Backyards

While the conservation of forests, farmland, and urban tree canopies is admirable and lives in the heart of every environmentalist, we should understand that these goals can become entangled with policies that benefit white communities and harm Native Americans, Black, immigrant, and low-income communities. In local zoning and land-use planning discussions today, suggestions to limit local population growth and preserve neighborhood character are commonplace. This thinking will not help us build the inclusive and diverse movement required to prevent a climate catastrophe.

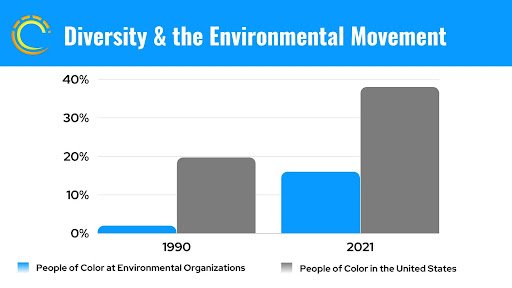

And we have a lot of work to do. Diverse members of environmental organizations represent just 16% of staff despite representing 38% of the total population.8 Environmental organizations are more than 30 years behind in catching up with the country’s diversity.

Graph created by C3 as a part of the Climate-Smart Zoning webinar

I spent the first ten years of my career as an advocate for forest protection. Some of my best friends and memories are from that time, but in 2022 when the biggest environmental problems are global in nature, the need for equity should be clear to everyone. We can and should do better.

Environmentalism today still spends the majority of its time advocating for where people shouldn’t live, but to address climate change, this mindset needs an overhaul. Virginia will add another 1.2 million residents by 2040. Where will these people live? Unless environmentalists become staunch advocates for density, affordable housing, and zoning reform, more and more Virginia residents will move further into our counties, where new housing developments will remove even more forests and farmlands and where residents will continue to rely on their cars as the primary mode of transportation with longer and longer commute times.

To change everything, we will need everyone. If we do our jobs well and create local climate, housing, and transportation policies which promote both affordability and climate leadership, the people living in cities across Virginia will do so with a lighter footprint on the planet. It’s time for environmentalists to start advocating for where people should live instead of just where they shouldn’t, and together we can build a broader movement for more livable, just, and sustainable communities.

Footnotes/Recommended Reading:

3 - https://demographics.coopercenter.org/virginia-population-projections

5- https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2021/05/return-the-national-parks-to-the-tribes/618395/

7- https://www.splcenter.org/20100630/greenwash-nativists-environmentalism-and-hypocrisy-hate

C3 and Livable Cville’s Climate-Smart Zoning Webinar Recording from June 7, 2022 on our YouTube Channel